To be a valuable global supplier

for metallic honeycombs and turbine parts

Release time:2026-01-13

In shielding design, more is not always better. This becomes especially clear when dealing with ventilation openings.

Electromagnetic shielding vents are often selected with one goal in mind: maximize shielding effectiveness. In practice, this approach can create a different set of problems that only appear after the system is assembled and running. Overshielding is one of them.

In many projects, vent selection happens late. Thermal calculations are finished, enclosure layouts are fixed, and EMI requirements arrive as a final constraint.

At that point, the safest decision appears to be choosing the highest-rated electromagnetic shielding vent available.

On paper, this makes sense. In real systems, it often causes trouble.

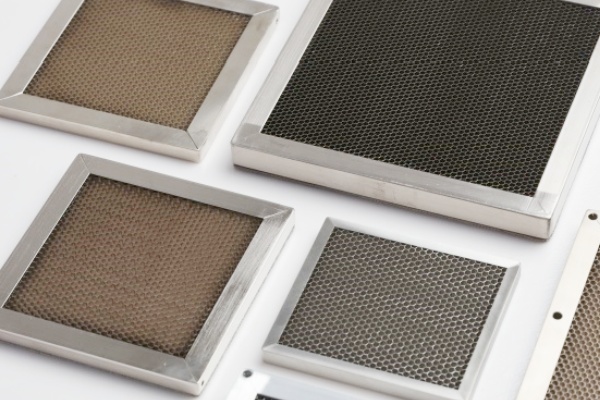

High shielding levels usually come with smaller vent openings, deeper waveguide structures, or denser internal geometry. All of these affect airflow.

The most common consequence of overshielding is reduced airflow.

A vent designed for extreme shielding performance may significantly increase pressure drop across the enclosure. Fans work harder, airflow paths change, and hot spots appear where they were not expected.

These issues rarely show up during component acceptance. They appear during system-level thermal testing or, worse, after installation in the field.

When that happens, the vent becomes a target for modification.

Once thermal problems appear, changes are often made quickly.

Vent openings are enlarged. Additional holes are added nearby. In some cases, shielding vents are replaced with standard ventilation panels without revisiting EMI requirements.

At this stage, the original shielding design no longer applies. The enclosure may still pass mechanical inspection, but its EMI performance is compromised.

Many EMI failures attributed to “poor shielding design” actually start as overshielding problems that triggered uncontrolled changes later.

Highly shielded vents tend to be heavier and more rigid. This can create mechanical stress at the mounting interface, especially on thin enclosure panels.

If the enclosure surface is not perfectly flat, contact pressure becomes uneven. Electrical continuity suffers, even though the vent itself is well designed.

In these cases, increasing shielding performance on paper leads to worse real-world results.

Dense vent structures are also more sensitive to contamination.

Dust, moisture, and debris accumulate more easily in narrow channels. Over time, airflow degrades further, and corrosion risks increase at contact points.

A vent selected purely for maximum shielding may perform well initially but degrade faster in actual operating environments.

Effective vent selection starts with understanding the frequency range that matters.

Many systems do not require extreme attenuation across a wide spectrum. What they need is reliable shielding at specific operating frequencies, combined with stable airflow and grounding.

Selecting an electromagnetic shielding vent that matches those needs — rather than exceeds them — often results in better overall system performance.

One reason overshielding is common is that it appears to simplify decision-making.

Choosing the “strongest” vent avoids discussions about airflow, grounding, and installation constraints. Those discussions still happen later — usually during troubleshooting.

Overshielding shifts problems downstream instead of solving them.

In real projects, electromagnetic shielding vent work best when they are:

Selected based on required frequency range

Compatible with enclosure airflow design

Easy to install with reliable electrical contact

Mechanically appropriate for the panel structure

Stable under environmental exposure

More shielding is not automatically better shielding.

Vent openings are already compromises in a shielded enclosure. Improper vent selection, especially overshielding, often turns a manageable compromise into a system-level problem.