To be a valuable global supplier

for metallic honeycombs and turbine parts

Release time:2026-02-05

In aerospace work, weight is never background noise. Even small parts get questioned. Vent hardware included.

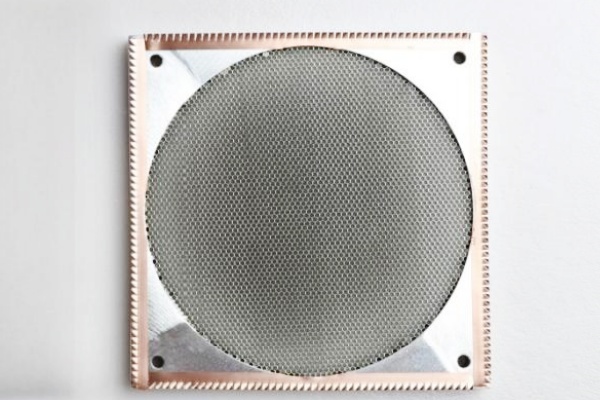

A Planar Waveguide Vent usually enters the discussion when airflow is needed but open holes are no longer acceptable from an EMC point of view. The question is not whether shielding is required—it always is. The real issue is how to keep it without adding mass.

A hole is a hole. Once metal is removed, shielding continuity is interrupted. Thick metal or deep honeycomb can restore attenuation, but weight rises quickly. That approach works in ground systems. In airborne or space systems, it often doesn’t.

The Planar Waveguide Vent relies on channel geometry rather than bulk material. If the channel stays below cutoff for the target frequency range, energy attenuates along the path while air still moves. No heavy block of metal required.

Most lightweight vent structures start with aluminum. It is conductive enough, light enough, and easy to form into precise channels.

The concern is mechanical behavior. Thin aluminum walls can shift slightly under mounting load or vibration. Usually small, sometimes relevant. When dimensional stability becomes critical, designers occasionally switch to stainless or reinforced variants, accepting extra mass for predictable behavior.

The decision is rarely about numbers alone. It is about how much movement the system can tolerate.

Cooling in aerospace electronics is rarely about “as much air as possible.” It is about predictable heat removal.

Channel depth, opening ratio, and wall thickness are adjusted to keep pressure drop manageable without weakening shielding. The Planar Waveguide Vent is tuned, not simply opened.

This balancing act often matters more than raw airflow capacity.

Launch vibration, thermal cycling, long service intervals—lightweight structures must hold shape. Shielding performance depends on geometry staying where it was designed.

In practice, slightly lower but stable attenuation is often preferred over higher performance that drifts. Surface condition, material stiffness, and manufacturing consistency all play into this.

A Planar Waveguide Vent tends to appear when:

airflow is necessary but simple apertures fail EMC

heavy shielded vents exceed weight allowance

high-frequency emissions need tighter control

consistency matters more than peak performance

At that stage, the vent is no longer just a thermal feature. It becomes part of the electromagnetic structure of the enclosure.

Geometry defines how a Planar Waveguide Vent should work.

Material and structure decide whether it keeps working after vibration, heat, and time.

In aerospace, that difference is rarely theoretical.