To be a valuable global supplier

for metallic honeycombs and turbine parts

Release time:2026-02-03

In many EMC projects, enclosure shielding is treated as a closed problem.

Material selection, wall thickness, grounding, bonding—once these boxes are checked, the enclosure is considered “safe”.

Then the system goes into testing, and emissions still leak.

More often than not, the issue is not the enclosure itself, but the place everyone knew was there and still underestimated: the ventilation opening.

From an electrical standpoint, effective shielding relies on continuity.

As long as the conductive boundary remains intact, electromagnetic energy is largely confined.

Ventilation breaks that boundary by design.

Even with a fully metal enclosure, well-treated seams, and proper grounding, the vent area remains an intentional interruption. In EMC testing, that interruption frequently dominates the result.

This is why systems that look solid on paper still show localized radiation peaks near vents.

A common assumption is that small holes are harmless.

Electromagnetically, they are not.

Once operating frequencies increase, even a relatively small opening begins to behave like an aperture. Instead of “leaking a little”, it can couple energy efficiently, especially when internal sources sit close to the vent plane.

In practice, this shows up as:

higher emissions at specific frequency bands

directionality aligned with the ventilation surface

results that worsen as clock speeds increase

The enclosure still works—the vent does not.

Louvers are often chosen as a practical compromise. They improve airflow and offer some physical protection, but from an EMC perspective they introduce long, slot-like openings.

These slots are problematic because:

they support polarized leakage

attenuation varies strongly with frequency

performance is difficult to predict across bands

At lower frequencies, louvers may appear acceptable. As frequency increases, their shielding contribution becomes increasingly unreliable.

They solve thermal problems. They rarely solve EMC ones.

Another misunderstanding is assuming electromagnetic leakage spreads evenly across the enclosure.

It doesn’t.

EMI follows the lowest impedance path. Sharp edges, discontinuities, and open structures guide the field. Vent openings often become preferred exit points simply because they offer less resistance than the surrounding metal.

In many failed systems, the vent is not just a weak point—it is the dominant radiation path.

Adding meshes or thicker plates after a failure usually treats the symptom, not the cause.

The fundamental issue is that airflow paths are often left electromagnetically undefined. Air moves freely, but so does high-frequency energy.

This is where a structural approach becomes necessary.

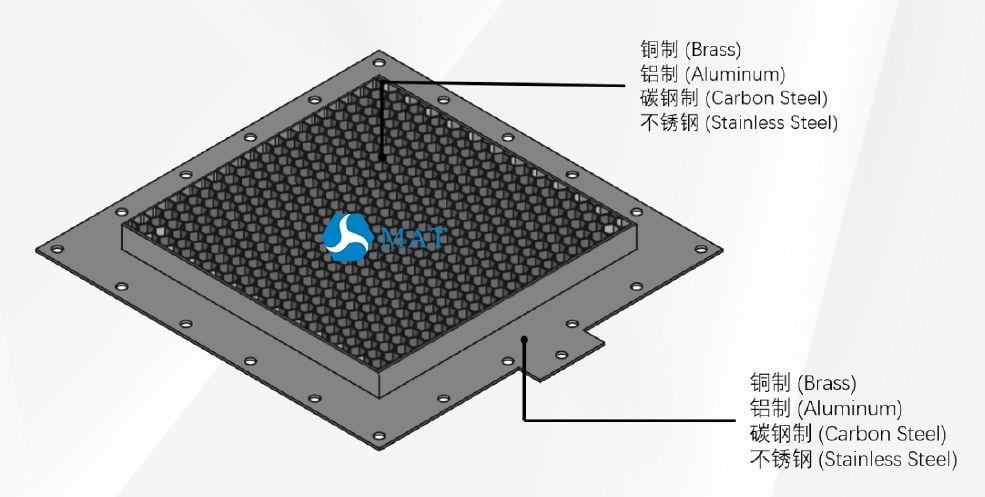

A Planar Waveguide Vent addresses the problem by geometry rather than brute force. By applying waveguide-below-cutoff behavior in a compact, flat structure, it limits electromagnetic propagation while preserving airflow.

Instead of trying to block EMI, it prevents it from forming a transmissive path in the first place.

Planar waveguide ventilation becomes relevant when:

operating frequencies are high and broadband

enclosure space is limited

airflow cannot be sacrificed

EMC margins are tight

In these situations, ventilation design directly affects compliance. Treating it as a secondary detail often leads to repeated test iterations.

A shield is only as effective as its most permissive opening.

In many modern systems, that opening is not a seam or a connector—it is the ventilation vent. Designing vents with electromagnetic behavior in mind is no longer optional. It is part of making the enclosure actually work.